Normative developmentalism’s assurance of chronological and progressive body changes that dominant narratives of growth present to children, where (healthy) children’s bodies grow into (healthy) adult bodies, was a promise that we, as adults, felt betrayed by in our own experiences – and, accordingly, wanted to interrupt with children. Our most urgent concerns continue to be:

When we offer developmental body logics that situate temporality as stable and predictable, we get to know bodies through an expectation for consistency and endurance: my body can do this right now, so it should continue to be able to do this; I feel comfortable in this body now, so it would be normal and expected for me to continue to feel comfortable in this body. These bodied relations premised on stability are not up to the task of relating with bodies as they become unstable and unpredictable.

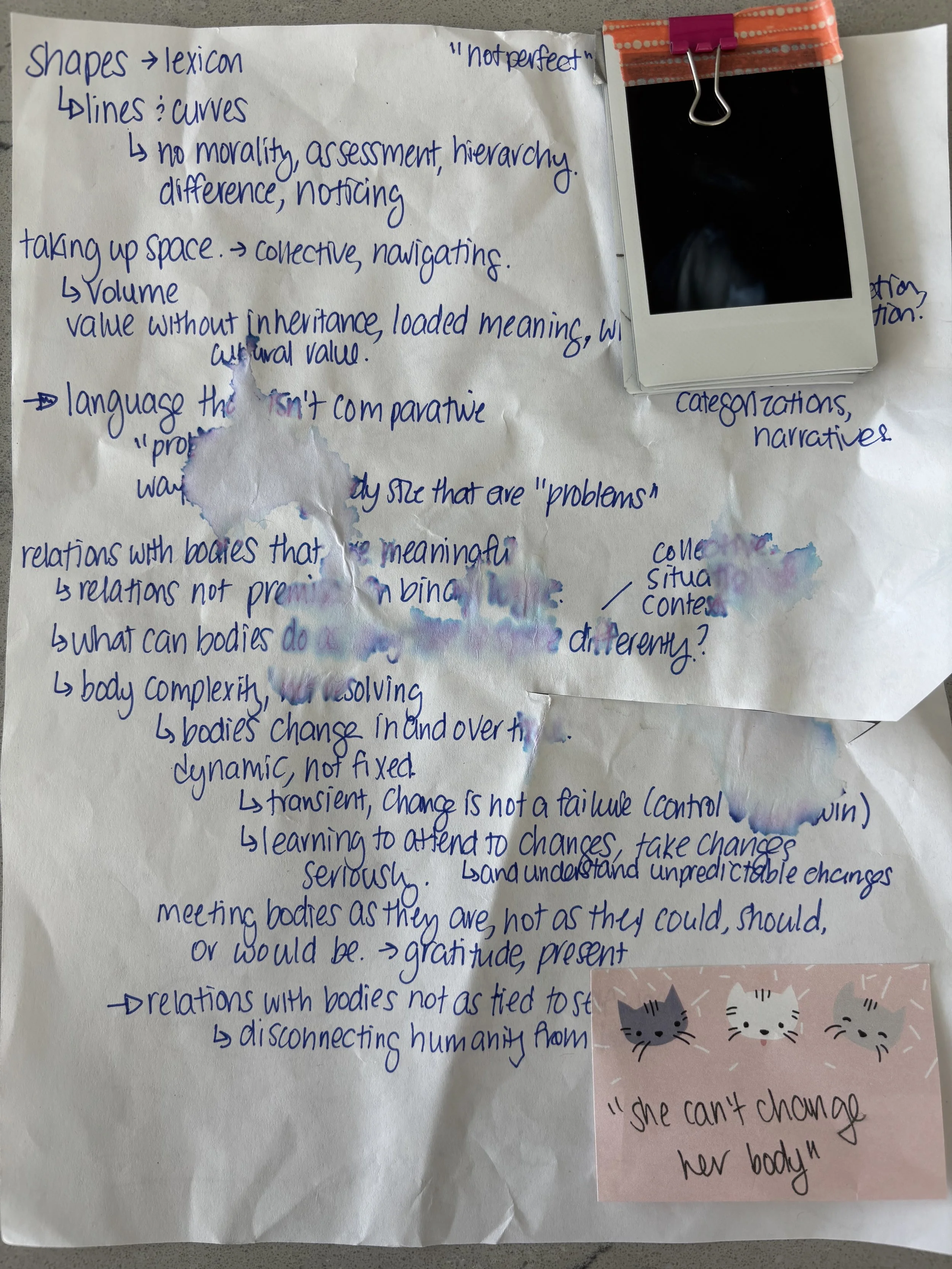

Developmental body logics that understand growth as a childhood experience, where comments like “when you grow up, you’ll be tall”, name body change as a bounded temporal period that ends at adulthood. This means that we get to know body change as a temporary condition that should, normally, end at adulthood. Body fluctuations after development’s promised adulthood finish line are, therefore, unexpected and abnormal. These teleological bodied relations do not affirm the reality of bodies as a forever shifting experience and they cannot hold the complexities of getting to know our always shapeshifting bodies.

Colloquialisms in ECE like “healthy habits start small” or “active children are active adults” are grounded in a body logic of investment, where we are assured that our responsible neoliberal biocitizenship practices as children will pay dividends into the future. If we practice body relations of compliance as children, we can expect our well-disciplined bodies to serve as commodities, as brokers of power, into the future. Knowing bodies as commodities breeds relations that objectify bodies, figuring bodies as artefacts that matter for their use-value. These bodied relations of capitalism and body-as-asset supersede and foreclose other bodied relations that cannot be commodified. It is these anti-economic, non-developmental relations that, we assert and hope, are important for living well together with children.

Context, Concerns, and Inheritances

Normative Child Development

We situate our project alongside a much larger collective push towards working with knowledges and relations that understand children outside of the logics of normative child development (Blaise & Pacini-Ketchabaw, 2025; Bloch & Whye, 2024; Nxumalo & Peers, 2024; Vintimilla, 2023). Child development has long served as the pre-eminent approach to understanding children’s bodies in ECE in Canada (Land & Todorovic, 2021; Land & Vidotto, 2021), couched inside ECE’s broader “dependency on child development as its primary source of intelligibility” (Vintimilla & Pacini-Ketchabaw, 2020, p. 630). Developmentalism, through its articulation of childhood as a universalized experience, positions a vision of the Eurocentric ‘ideal’ child as the referent that all children are measured against (Burman, 2016). This standardized understanding of childhood means that children’s experiences can be quantified, compared, predicted, regulated, and disciplined. Children who do not align with developmentalism’s normative understanding of childhood are marked as ‘other’ and their experiences of difference are framed through unjust and discriminatory deficit discourses, narratives of the at-risk child, and medicalized interventions (and logics of repair) (Nxumalo & Brown, 2019). Accordingly, when normative child development is the fundamental knowledge guiding ECE, the classroom becomes a space for assessing, regulating, and remediating children (Yoon & Templeton, 2024). This means that curriculum must facilitate children’s acquisition of skills, as determined by developmentalism, on a particular timeline, as determined by developmentalism (Fontanella-Nothom, 2024; Land et al., 2022). When curriculum is consumed by child development, “curriculum-making is stripped of explorations and experimentations that are not circumscribed as developmentally appropriate” (Vintimilla & Pacini-Ketchabaw, 2020, p. 633) and “relations outside the parameters of developmental psychology are made superfluous” (p. 633). Normative child development, as a logic and a structure, is, therefore, an incredibly consequential fulcrum of power dynamics in ECE: it presents childhoods grounded in whiteness as normative, deploys difference as an exclusionary mechanism, oppresses diverse lived experiences, and strategically curates curriculum as a tool of normativity.

Normative child development has intense and crushing consequences for how we get to know bodies with children in ECE. In our work, we found it ‘easy’ – apparent, familiar, relentless – to name how and when developmentalism informs relations with bodies. We could name events (ex. mealtime), routines (ex. circle time), rhythms (ex. transitions), activities, assessments, and structures (ex. licensing requirement to have a certain number of fine motor and gross motor activities each day) and readily note how they are informed by developmentalism. We could also trace the classroom arrangement, materials available, and storybooks for developmental logics, and we noted how we move, notice, and narrate in ways that echo developmentalism.

Studying normative child development for the bodying logics and relations it does and does not permit, we noted how relations of control, regulation, minimizing, instrumentalizing, linearity, and discipline did not align with our own shared, but not identical, pedagogical commitments. When we thought with our second research question, how might we continually work at co-creating and sustaining more livable –emplaced, fleshed, responsive, affirmative, and ever shapeshifting - bodying relations with children?, these extant relations did not, in our interpretation, create hopeful entry points for envisioning more equitable ways of getting to know bodies with children. Of particular trouble, for us, was how developmentalism positions bodies as predictable, where growth is linear and sequential.