Bodying and Subject Formation

And, when “it is through this relational movement that bodyings take shape, and here, in the ‘where’ a body will never quite reach, that movement overtakes the mover” (Manning, 2014, p. 181), how do we figure out how to get to know bodies, collectively, without stopping this movement or impeding these relational cascades that overtake? How do we do bodies, together, outside of subjectivities premised on already knowing bodies?

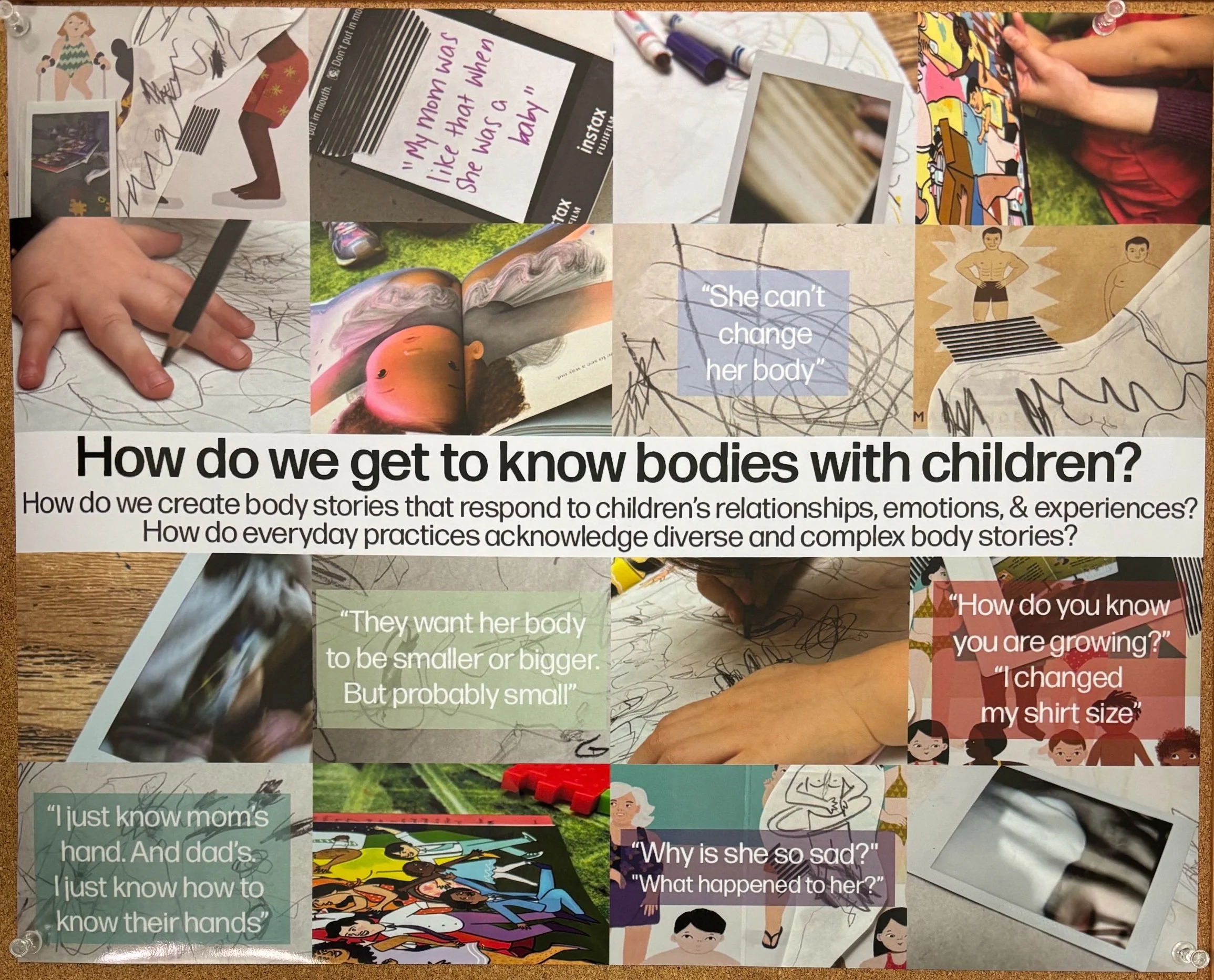

Within shifting relational bundles of bodying, movement, commons ,and worlding, Manning (2014) proposes that subjectivities – processes of articulating the subject – are further tangled with relational complexities. For Manning, “there is here a quality of body-moreness (not bodylessness), a bodying in motion that expresses itself with a quality, perhaps, of effortlessness, effort less because it is not the subject, not the pre-formed body doing the moving, but the relational field itself that moves” (p. 172). Bodying undoes normative subject formation; it refuses status-quo methods of describing the (human) subject-with-a-body in ECE. Well-worn refrains of the ‘graceful’ child (smooth fine motor skills, intentional movements, sense of rhythm), the ‘clumsy’ child (uncoordinated, lacks body control, abnormal motor skills/development), the ‘athletic’ child (talented, highly developed motor skills, motivated, competitive), or the ‘high energy’ child (full-body movements, refusal or inability to be still, excess or unplanned movement) do not make sense to bodying’s relationalities. Vintimilla’s (2023) question, “what subjective processes are possible and what are impossible to imagine?” (p. 23), echoes loudly here: how we get to know bodies with children is painstakingly entangled with how we get to know – and the forces of exclusion that delineate - the child, man, and human.

In our work, tending to how bodying and the subject coalesce is important because ECE is an educational project and education is a mechanism of subject formation (Arndt & Tesar, 2019; Nxumalo & Nayak, 2024; Vintimilla et al., 2023). As Biesta (2022) writes, “without a concern for the subject-ness of the student, that is, for the possibility for the student to exist as subject, education ceases to be educational and becomes the management of objects, effective or otherwise” (p. 8). This means that we cannot parse bodying from subject formation, nor can we suspend the contexts and histories that make (and prohibit, exclude, govern) particular bodies and subjects in ECE. Bodying is, then, intensely political in ECE because bodies co-compose with subjectivities, where subject formation threads through the everyday ‘stuff’ of education. Manning (2016) proposes “that an approach that begins in the field of relation is precisely political because it does not begin with the agency of a preconceived group or solitary identity” (p. 123). This political risk, the gamble of doing’ bodies that do not make sense to conventions of the taken-for-granted body used/controlled/inhabited/owned by the taken-for-granted Eurocentric, neoliberal subject, becomes possible when a relational nexus nourishes the work of doing body-as-a-verb.

Taken-for-granted subjectivities that crumble into the captures they self-mandate rely on what Taylor (2020) describes as “the lofty epistemological traditions of Cartesian ‘rational Man’, who thinks about and acts upon the world from transcendent heights” (p. 344). Iteratively constituted with neoliberalism, neocolonialism, and capitalism, these dominant subjectivities infuse ECE with an imperative to create self-governing and self-responsible subjects (Vintimilla, 2014). Particular to childhood, child development dictates the normative child subject (Burman, 2016), capitalism designates the child as an economic subject (Powell, 2016), and bodied performances represent children’s morality and citizenhood (Leahy, 2014; Powell, 2014). For Manning (2014), these subjectivities rely on the humanist “habit of placing the subject first, of situating the subject as outside the activity of its bodying” (p. 178). In our work, figuring out how to attune to processes of bodying and subject formation became a complex question: how do we create possibilities for bodying-subjectivities outside of stable referents and inherited logics – or, as Manning offers, that “exceed any pre-supposed starting point” (p. 183) – with children while responding to the everyday relations and conditions that nourish, spur, trip, and capture bodying as a radically relational activity in ECE?