Bodying and Relations

Put differently: how do particular collectives and relations create particular possibilities for doing bodies in ECE, and how do specific bodyings make specific collectives and relations possible and impossible with children? And – how do we tune to, stand for, take the risk of, or interrupt these conditions and collisions without returning to the chronic containment and predictability of body relations and logics that underpin dominant approaches to getting to know bodies in ECE?

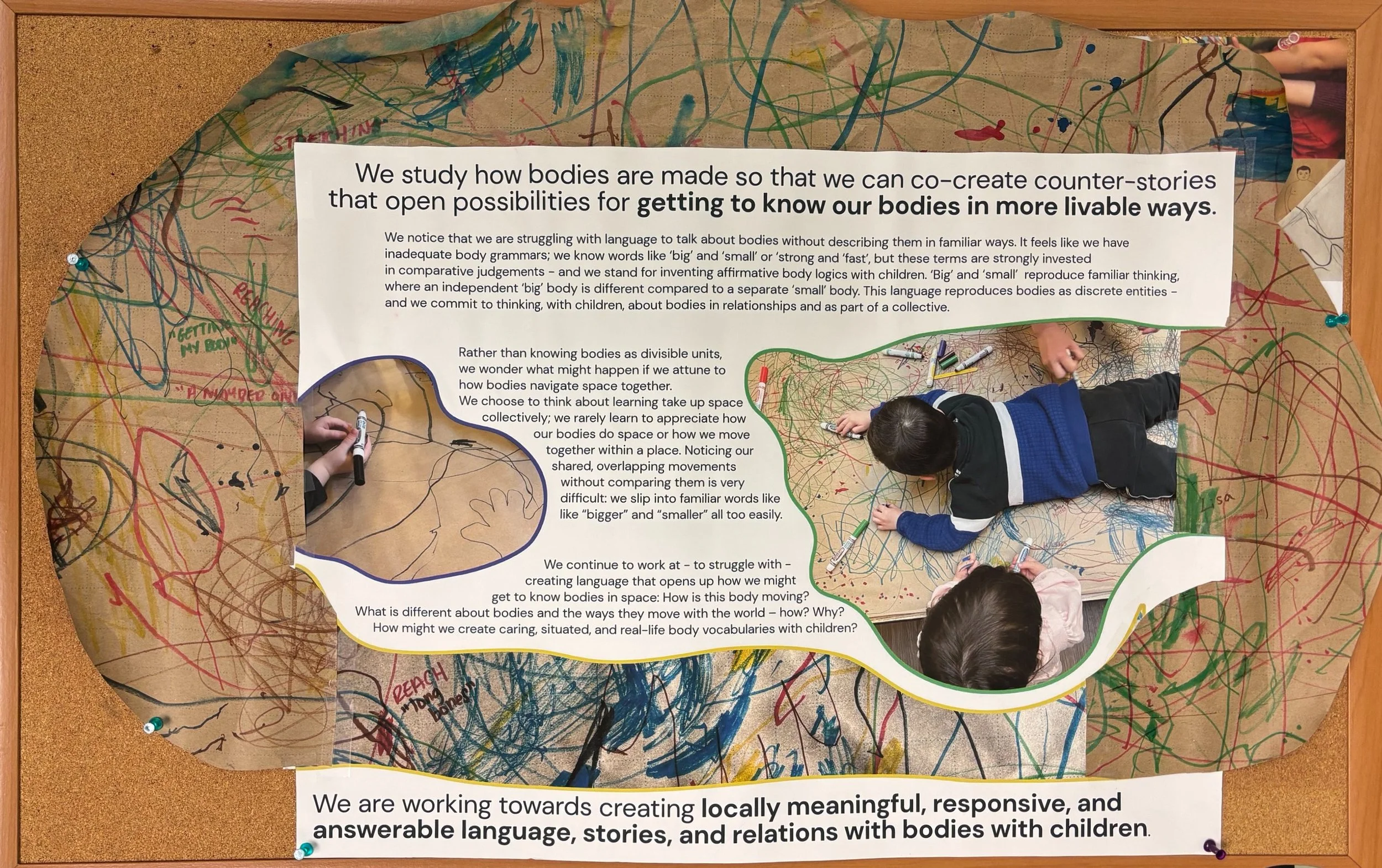

With Manning (2014) bodying is radically relational. A body “cannot be thought outside of its implicit co-tuning with the associated milieu – the relational field or interval – of its emergence” (p. 172); bodies shape and are shaped within situated, intricate relations. In our work, getting to know bodying as a relational process emphasizes that bodies are collective activities and concerns, which names an otherwise to dominant discourses in ECE that position bodies-as-individual (ex. gross motor skill assessment/performance; individualistic responsibility for body shape, health, fitness) or bodies-as-isolated (ex. agency to control our own bodies independent of what surrounds us; self-regulation as an individual skill detached from other bodies). Importantly, when bodying and relations forever tangle and re-tangle, we need to tune to how our practices for encountering bodies impact how we understand collectivity. If a collective cannot be a stable, already known and knowable gathering of stable, already known and knowable bodies, then status-quo methods for how we get to know bodies and collectives are put at risk. For example, prevailing ECE approaches to understanding bodies and collectivity know bodies as disruptive to an idealized collective, where individual children’s bodies ‘interrupt’ or ‘do not fit’ into a vision of the collective as calm, harmonious, or shared. Often the collective is named as ‘we’ and bodies are named individually: ‘we were getting our winter jackets and boots on to go outside, and this child needed to remove their snow gear to use the bathroom’. Bodies overflow or agitate the collective, but the collective seems to persevere. Towards re-crafting collectivity with bodies, we think with Manning’s contention that “relational movement is always a movement of thought, and each movement of thought is the generating of an in-act of movement-moving” (p. 172). Specificity and emergence create; bodying and relating are generative processes, ongoing in their coming to form and decomposing as bodying and relating participate in worlding.

For us, this underscores important questions about how we understand collective-making as/with bodying with children: how do we create a commons that is both capacious and particular, and not-yet-known and oriented to justice, where situated relations and bodies co-compose, inventing and re-inventing the context, accountabilities, and commons? Community and collective-making matter deeply to our ECE context because how we understand the labour of commoning is political (Vintimilla & Berger, 2019). Vintimilla (2023) throws us the question “how do the ways we imagine the commons affect our relation to knowledge and thinking in early childhood educational contexts?” (p. 192). When community is named as an already known or already present project, then already known dominant relations (ex. harmony, consensus), knowledges (ex. developmentalism, corporatization), and subjectivities (ex. innocent child, maternal educator) are reproduced by and to sustain this pre-existing, comfortable conceptualization of community (Vintimilla, 2023). Working with Manning’s (2014) articulation of bodying and relating as generative processes-in-motion, we take seriously that there is no promise that collectives will be liberatory, just, or affirmative; maintaining the status-quo is an event of production, as is the risk of producing increasingly insidious and totalizing relations of governance and conformity. This means that, as we take up the question of doing bodies with children, we want to work at creating and sustaining relations and collectives that are necessarily and generatively uncertain – where this uncertainty opens a space for working otherwise at bodying, relationality, and collective-making. Uncertainty – defamiliarizing, interrupting, the not-yet-present – is not a relativist, hollow, or organic force. From Taylor (2017), we learn that commoning requires a “persistent commitment to reaffirm the inextricable entanglement of social and natural worlds –through experimenting with worldly kinds of pedagogical practice” (p. 1455). From Vintimilla (2023), we carry the question “could we think relations in early childhood from this void that does not ask to be filled with meaning making and instead create space for relations that come to be through its incommensurabilities, its impossibilities?” (p. 187). Taken together, our work of figuring out how we might continually work at co-creating and sustaining more livable –emplaced, fleshed, responsive, affirmative, and ever shapeshifting – bodying relations with children is layered with questions of creating commons that do not foreclose ethics of entangling, worlding, experimenting, resisting, responding, and disorienting.