Escapable Body Temporalities

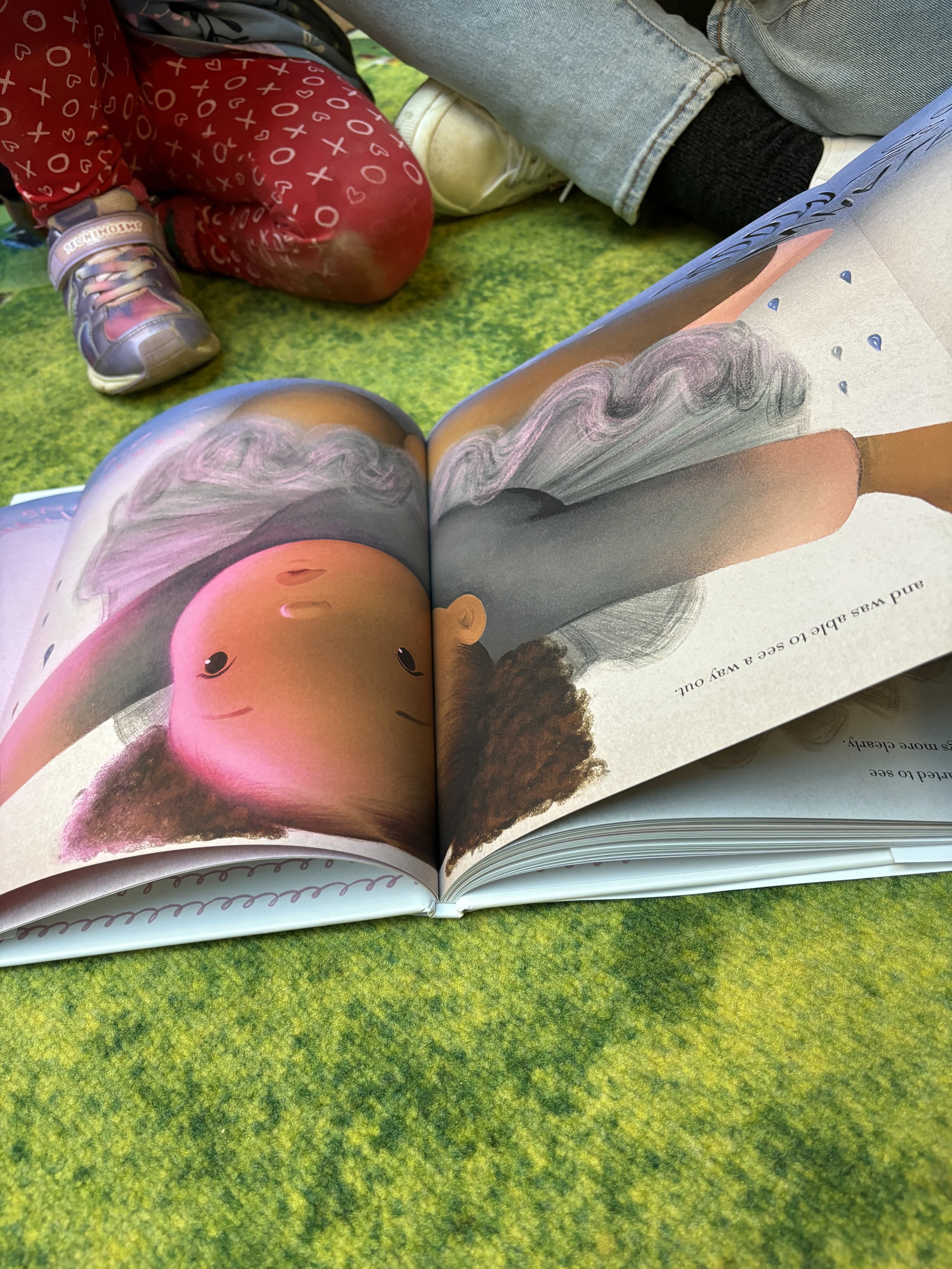

One morning, we were spending time with the book Big by Vashti Harrison. A few children, 2 educators, and I were sitting together on the floor. We had Big open on the floor in the middle of our squeezed-in bodies gathered all around the book. Big tells the story of a young Black female dancer’s incredibly complex experience of her ‘big’ body.

A few minutes into our collective reading and subtle jostling for floor space, one of the children sighed, softly said aloud ‘she can’t change her body’ stood up, and walked away. It was an ordinary, modest, swift moment. When one educator and a researcher shared with the child that her observation that ‘she can’t change her body’ was interesting to us, she was skeptical. She was frank in letting us know that, for her, this was one of the least interesting ideas from our work together so far. We were and remain, purposefully, unsure which body narratives and collisions this child was responding to with ‘she can’t change her body’: who cannot change her body? The dancer in Big? The children whose knees and shoulders were bumping into one another? Our larger adult bodies and the ways we do and do not bend? Intentionally focusing on the work of bodying pedagogies, we moved from trying to discern exactly what happened in this moment to thinking intentionally about how relations with changing bodies are made possible and impossible in the collisions that ‘she can’t change her body’ spawns. We did not want to psychologize or diagnose what the child was thinking as she quietly phrased this bodied relation, but we did want to think about what happens pedagogically (Berry et al., 2020) in this studying, negotiating, bumping, and refusal of bodied logics.

‘She can’t change her body’ became a beautifully annoying wondering to us as researchers; it is riddled with contemporary contradictions that have intensely complicated our pedagogical concerns with body logics and temporalities. Who is the subject of this proposal – and how does this shift if we read this as a diagnosis of a complacent or trapped person (‘she can’t change her body’), an accusation rooted in how dominant body discourses theorize an individual’s role in body change (‘she can’t change her body’), or a marker of how the charge of changing a body exceeds our conception of the individual (‘she can’t change her body’)?

At a status-quo surface level, ‘she can’t change her body’, seems readily aligned with popular body positive and wellness ECE curriculum in Canada. As an extremely broad overview, current body positive curriculum approaches tend to emphasize that educators and families should be positive about body diversity (ex. “all bodies are good bodies” [Provvidenza et al., 2021, p. 7]) and should teach children how their behaviour and agency is connected to physical and mental health, nutrition, physical activity, and wellness (ex. “making healthy choices about food and physical activity…and taking time to rest” [Physical and Health Education Canada, 2025, para. 6]). Read alongside dominant body positive curriculum, ‘she can’t change her body’ can be an affirmation of body neutrality, body acceptance, and evidence of this child’s sense of belonging, care, and empowerment. In this same moment, the paradoxical function of body positive curriculum locates the body as an object or as property that a disciplined, healthy child can appropriately mediate (LaMarre, Rice, & Jankowski, 2017). Reiterating dominant biopedagogies and biomoralities (Rinaldi, LaMarre, & Rice, 2016), body positive frameworks center developmentalism’s normative body as the healthy body and position difference as a diagnosis or deficit worthy of intervention. Here, the utterance ‘she can’t change her body’ can be read as failure: she cannot perform her body as a proper child subject should. Entangled with this interpretation, we can also hear ‘she can’t change her body’ as a move away from individualized approaches to body positivity, where curricula outline how education can create holistic wellbeing by addressing systemic health structures including policy, access, and accountability (ex. the Canadian Healthy School Alliance, 2021). Here, ‘she can’t change her body’ is a gesture to wider structural contexts of health and wellbeing, and complexifies the taken-for-granted neoliberal emphasis on individual responsibility for maintaining control of and regulating our own bodies. While we note the shift in body relations made possible in body positive and systemic curriculum approaches in ECE, we are very suspicious of romantic, reductive, or recuperative body pedagogies. We are concerned that body relations and logics of normativity, governance, object, property, and the disciplined subject are left intact through body positivity and systems-level interpretations.

In thinking through what holds pedagogical gravity for us in ‘she can’t change her body’, there is a whisper of worldmaking and indiscernibility at play when the question of how we get to know changing bodies is at risk – what if it is change that we study, make slippery, and take as a proposal towards affirmative and resonant bodying pedagogies? Of specific ethical and political concern for us is how body fluctuations, and desired or discrepant or strange or energetic trajectories of change, are a mechanism for bonding bodies with subjectivity with personhood in ECE. This nexus, this collision of body temporalities with bodying pedagogies, is where the proposal of escapability entered our thinking: what becomes possible for getting to know bodies with children when body temporalities – how bodies do time, change, flux – are not determinate, inevitable, or perpetual? How might escaping body temporalities be a move towards bodying pedagogies with children?

From Lind and colleagues (2018), we learn that “through valued relations and against standards of success, linearity relies on respectability to produce socially legitimized subjectivities” (p. 182). There are strong parallels to child development, where bodies become public proxies for discerning one’s value as a contributing neoliberal subject: if you work hard to build a thin body as a child, you will prove you have the grit to succeed at creating a capable, desired body as an adult. Relations of morality, perceptibility, acquisition, and power stem from this articulation of linear body logics. While in the question of ‘she can’t change her body’, change is parsed from the subject and positioned outside of agency and accountability, change is still imbued with a kind of necessity. How then, do we attune to alternative relations with bodies and bodied rhythms that do not invest in the requirement that bodies should change in certain ways, even if how that change unfolds is not solely one subject’s imperative? What relations with bodies might matter when we decline the arrogant humanist insistence that while she can’t change her body, we know how her body should change?

Rather than only cleaving body change from moral character, what bodied relations become possible when how bodies change is not already determined?

Crowded around the storybook Big, what if ‘she can’t change her body’ points at the grave uselessness of logics of body change loyal to the purview of the isolated, moralized, neoliberal citizen child subject? What if ‘she can’t change her body’ illustrates how little sense singular understandings of agency, responsibility, and legitimacy make as children’s bodies bump against one another while engaging with a storybook that interferes in dominant discourses of universal, normative body growth? What if responding within this bodied reading event incites processes of change that do not subscribe to the kinds of body change – regulation, discipline, morality - available to the legitimized subject because the production of a legitimized subject is not relevant to how bodies collide and shift in this moment?

We wondered how we might craft bodied relations where change does not have to unfold along knowable grammars of disciplinarity and inevitability. ‘She can’t change her body’ brought us to wondering our inherited chronological logics of body change. Prevailing discourses on body change assert that bodies change within a lexicon we already know: they mature, they age, they expand, they wither, they diet, they die. The backbone of how bodies change is not, in dominant logics, up for debate. Biology, epidemiology, development, economics, and humanness define, anticipate, and quantify bodily change. As we think with ‘she can’t change her body’, we wonder what happens when the word ‘change’ is equally at risk as ‘she’. What if we get to know how change and bodies entangle outside of an essentialist correlation? What if we embrace that bodies constantly change but insist that we do not already know the processes nor terrain of bodied change?

With Fox (2018), we learn that normative temporal relationships with fat position the body as “an imaginary state of future achievement” (p. 222). Colonial and capitalist chronologies demand that bodies are continually worked at in the name of preserving their moral, aesthetic, and commodity value into the future. This mirrors the linear logics of child development: fit children become fit adults. The scale of recognizing how bodies change remains cemented in the individual subject, and relations of deferral, predictability, and mastery thread through the illusory but inescapable iteration of the future forecasted by these linear body logics. We wonder, then, how we can spur pedagogical conditions where body changes that manifest this always aspirational tomorrow are not required and the agential human might not be the sole arbiter of this change because these two conditions – known change and known subjects of change – stop making sense? If we want to interrupt both the subject formations that require body change for legitimacy as an agential subject and the contention that body change must realize pre-determined futures, how might we get to know bodies with children? If dominant enactments of the subject with a changing body fail, how might we craft bodied relations within a commons?

What relations with bodies become possible as we figure out, together, how to engage changing bodies and the non-linear rhythms that make and are made by bodied change as a collective practice?

What if, as we gathered around the storybook Big, ‘she can’t change her body’ orients towards the inadequacy of extracting what is collective from changing bodies? If she cannot change her body because neither subjectivity nor change or bodies are fragmented, then how might we think body changes, rhythms, and relations as generative of collectives? If bodies change in concert with other changing bodies, change escapes from the borders of a singular body but bodies cannot escape from change processes. How might being implicated in a collective of bodies that articulate and are articulated by how change comes to matter require us to work at building otherwise body logics, times, and rhythms adequate to bodied change as shared world-making? How might we co-create relations of escape, where eluding taken-for-granted logics for understanding changing bodies (ex. child development, biopedagogies, body positivity) is a generative, inventive charge that incites body relations and logics other than familiar conceptions of escape as eschewing or critiquing or rescuing? The incredible paradoxes that ‘she can’t change her body’ compounds and the trouble it affords our thinking escapable body temporalities become palpably meaningful for studying and proposing otherwise bodying pedagogies with children.